Zhoobin Abdiani: I would like to start the discussion by asking, what made you interested in the still life genre? Because basically you introduced yourself to the world of photography in 1995 with the brilliant Venus Inferred project, how did the transition from personal life to still life happen for you?

Laura Letinsky: It didn’t feel like that much of a shift because as I worked on the project of couples, I became increasingly interested in how the space—the people’s home—described so much more that what started to feel like a “camera face” for all of my subjects. In 1996 I began using a large format camera that allowed me to control the focal plane. The composition of the space onto the photographic surface gave me more latitude to speak to how the photograph informs and directs us. From the Venus Inferred series that built on pictorial traditions, from mainstream films and Renaissance religious paintings, I understood how pictures influence not only other pictures, but our idea of who we are. The Northern Renaissance tradition that focused on the still life was a precursor to Elle Décor and Martha Steward catalogues, insisting on the “invention” of photograph so as to communicate particular, consumerist, values to a wide audience. I wanted to make photographs that unsettled the perfect narratives described in popular media. To complicate one’s ability to read the scene as natural, and instead, speak to the seduction, formulation, and provocation of photography. The issues feel the same to me across these seemingly different subjects in that photography is the medium that conveys the message and it affects us societally and as individuals.

– How did you take photos when you were a student? Is your current style of photography in line with your student performance or have you had a lot of rotation in your photography style?

– When I was a student, I fell in love with Diane Arbus’ work. The vulnerability with which she approached, and conveyed her subjects was unsettling in its precision. Like a razor cut. My training was in a modernist American photographic tradition and so Gary Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Joel Meyerowitz, and such were the gods. It wasn’t until graduate school that a larger discourse opened up and I realized the ocean that was the art world including critical, theoretical, and political approaches to image making. For me, this was vital as I’ve always wrestled with justifying art, the what-is-ness of it. What is its function…. There’s a pragmatic, utilitarian in me that needs to understand the larger context for art’s making and reception vs. an art for arts sake attitude. I understand the discipline as a form of communication akin to writing or music and believe that it doesn’t happen in a vacuum, rather in a set of relations and affects.

That said, looking back, how the photograph “is” in the world has always been a fascination. First, it was the ability to stare. Especially as a woman, looking is discouraged whereas men are able to do so without restriction. The camera enabled me to engage in this activity. As I worked, the particularity of how the camera described the world—not natural nor innate—it’s way of describing and how it shapes our understanding, this is why I make pictures.

– As you mentioned as a woman you have had a harder time getting ” Looking ” socially than a man. I would like to ask, has this patriarchy ruling the society – even in extended societies – had a direct impact on your way of looking at art making? Maybe a critical reflection or something like that.

– Absolutely! I was interested, and still am, in how and why women are looked at and men do the looking. An essay by Laura Mulvey from 1976, On Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, proposed that society is structured so that men have the power to look, and women are made powerless through being objectified for the male gaze. While this essay has holes in it, certainly there is a HUGE market for images (pornography, men’s magazines, etc.) that services this whereas for women, looking at other women is usually staged as a different kind of desire, for clothes, being made to feel inadequate physically, etc. Why is it that men are enculturated to feel pleasure at looking and the same doesn’t exist for women?

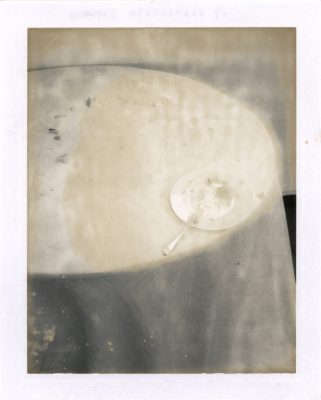

– Why have you based the “Culture of the table”, which has a long root in the history of art, on the principle of destruction and ruin in your pictures? What does this attitude of yours towards the destruction of objects and materials originate from?

– The illusion of the cornucopia awaiting the viewer’s consumption is problematic on many levels. The longing for this perfection leads to a dismissal of life in all its wonderous “imperfections.” My table scenes are, to my mind, less about destruction, that about having had these pleasures and appreciation for and of them in looking back, as well as looking forward. Not only accepting that the world, our immediate circumstances are never perfect, but embracing this as a necessity of being alive, this is vital for me. I want to present an alternative to the frenzy of consumer culture always seeking the new as it throws away the old, this built-in obsolescence leading to humanities ruin and deep personal unhappiness. Photography’s role in this has been integral, indeed, I would argue, its “invention” has been to promote unattainable fantasy so as to make us good consumers.

I long for a world that welcomes stains, wrinkles, scars, blemishes, all as signs of a life (well) lived. For the fantastical perfection of photography to be seen as tantamount to death. And a full, holistic sensorial experience that includes taste, smell, touch, sound, sight, etc. as really living. In the present tense.

– I’m aware of your interest in imaging practice preceding photography, can you explain about that?

– It’s theorized that there is no new, that everything we have and know is descended from what came before. As I understand, photographs are beholden to painting with formal, narrative, and perspectival cues, as well as subjects, ideologies etc. interconnected. My interest in other imaging technologies is to try to understand what these modes do, that is, how they communicate. Not just what is pictured, or formal information, rather, the reason for this particular kind of image within this particular context.

I looked to painting, and other modes of picture making to try to understand how I could make images to deal with issues in my/our world. More recently, I’ve become really curious about other modes of depicting time and space, including that of orthogonal perspective and pattern making. Anaconism, the prohibition of depicting animate objects is especially interesting to me as it was adapted by and through Catholicism’s urgency to make tangible those narratives as these are the strategies that have led us to photography.

– Do you think your recent curiosity makes you think about other genres of photography? Because basically, the medium of photography itself has a direct conflict with the issue of time, or do you want to stay in Still life for now and search time and space in this area?

– I am interested in the proposition of photography, that time is stopped, that the fantastical moment pictured is held as a possibility (even as we know it is unattainable). The still life affords me the space to consider this, the possibility of multiple viewpoints, of unsettling the hegemonically constructed stability of the image to instead move towards more experiential and richer kinds of seeing and being seen.

– Your still lifes are actually a reminder of a celebration in which consumerism has reached the highest possible level, more than introduction to the object and we see the solitary life of things after that feast, I would like to know what feelings these unconventional views evoke in you? And where did the first idea come from?

– My interest in the history of western European painting, as well as modern and post-modern including structuralism, deconstruction, etc., opened up ideas about the world and how we communicate through words and images. I understand photography as a language, and as a language, there are certain things it can do, and certain limitations. Authors and artists from Walter Benjamin to Lauren Berlant, Edward Said to Foucault, Rosalind Krauss to Deleuze and Guattari…and so many many more….

Dealing with the time I live in, I feel, if not an urgency, a need to address where (I think) we are. Questioning societal edicts, pleasures, rules and regulations, etc, in relation to power structures, those kept outside of affluence, and so on, these I think about what is left, what we have to work with, the reckon with what we’ve inherited and how to resuscitate, compost, reconfigure so as to, I hope, make a better worl

– Your photos in several projects contain a biting critique of unbridled consumerism, But they are also eye-catching photos; In your opinion, is it possible to show such a critical approach to an important issue in contemporary human life with eye-catching images?

– Photography is, if nothing else, a desire-making machine. I too love it for its seductive powers. Christian Metz wrote, The Photograph as Fetish, in which he articulates how the photograph functions both as a Freudian and a Marxian fetish object. Certainly the frenzy of image making attests to its conflicted role as a never-satisfiable-need/pleasure such that wanting is the goal. To rif on Langston Hughes, what happens to a desire satisfied? Does it disappear? We are a people who want “want.”

In my pictures, I try to stage this conflict such that if you want what is presented in my images, instead of longing for a fantasy, you are longing for what you have and might encounter satiation. Or the realization that the fantasy you long for is in you, in engaging your world, what you have and have experienced and will experience.

– The way you arrange things on the table and, accordingly, your compositions of still life is based on a photographic logic and contradicts the pictorial tradition of this genre. How do you see the importance of the photographic seeing in your photos?

– Absolutely! I want to confound the hegemonic authority of the single lens static framing that the photograph normally (to the nth degree as the medium is irrepressibly monolithically omnipresent) present. I want the jiggle of not everything according to a single point of view to cause a sense of unease, a mistrust of what the photography portends or promises.

– Apart from the visual world of painting and cinematography, how is your relationship with the world of literature? And has literature had a reflection in your outlook?

– Literature, and writing, is huge for me. An avid reader as a kid, words lead me into different worlds and I hope, open up for me the ways that other people live and experience. It availed an understanding that what I think I know may not be so as there are other histories, politics, family structures etc.

– I’m deeply entrenched in trying to understand how language works. Not just the stories or essays, but how language can build particular kinds of thought and structures. Contemporary authors are of particular importance because I want to try to figure out the tactics they use now for world-opening and questioning. These include, Lydia Davis, Ali Smith, David Foster Wallace, Roland Barthes, Gertrude Stein, Diane Cooper, Danielle Dutton, Ben Lerner… so many! I also try to read other culture’s writings to expand my euro- and Ameri-centric perspective as I am aware that my upbringing and education reenforced somethings over others.

– Photography has always moved or wandered between the borders of objective representation and subjective representation, which orientation do you think your photos are more inclined to?

– I understand these categories as completely intertwined and in concert with one another. We are bodies and minds. One can’t divorce one’s influences and past from anything one encounters. The camera itself is not a truth, but a mode of description that has a 2000 year, or thereabouts, history. We do not see as the camera does. It is a mode that was designed to show the world in a particular way that through seemingly infinite insistence has been normalized as “the way we see.” And even if an image were completely objective—though I don’t know what that would be—it’s reception, or reading/viewing could only be understand as a fusion of subjective and objective.

– Have you ever thought about showing your still lifes in a medium other than photography? For example, installation art that can evoke a deeper feeling of matter and space.

– I’ve worked in other media, words, food, textiles, and ceramics. I disagree that installation art could evoke “deeper” feelings, rather, it would be different feelings. My work in still life developed out of an understanding of the genre, particularly as it arose in northern Europe in the 17th century, as well as its return in phases of modernism (eg cubism, Manet, Money), as a grappling with colonialism, the wealth wrought through global expansion in a Protestant culture that wrestled with how to display its riches (Simon Schama and Norman Bryson write eloquently about this), and a need to disseminate an ideology to inspire a capitalist work ethos. Also, there’s the disregard for this site such that artists could utilize the subject for artistic pictorial questioning and innovation.

The still life has long been associated with the domestic, the domain of women and as such, lesser than grand historical or biblical narratives. Yet, the subject is also of vital importance, indeed, integral to our survival as living entities. Home, love, these are arenas that we consider individual and idiosyncratic yet the behemoth of culture produced around them bely the fact that these arenas are highly controlled and formulated, foundational to the societies in which they function. These tensions interest me as they continue to play out on minute as well as global levels.

Everyone is a photographer, and yet most images repeat vs. reveal…. I hope that by making images that question our perspective as well as that of the photograph, others are engaged in what matters.